What Rural India Taught Me About Public Health

What Rural India Taught Me About Public HealthBefore coming to India, I thought I understood how to think about public policy. I had studied economics, worked in empirical research, and was halfway through my Master’s in Public Administration in International Development at Harvard Kennedy School. But there’s a certain clarity that only comes when you leave behind your spreadsheets, set aside your theories, and begin listening (truly listening) to the people for whom policy is meant to serve.

Over the summer, I worked with The Antara Foundation (TAF), a nonprofit dedicated to improving maternal and child health outcomes in India’s public healthcare system. My primary project was to develop a framework for monitoring the experience of care: how people feel and what they experience when they engage with healthcare providers. But in truth, what I learned went far beyond my project brief.

At Harvard, I’d been introduced to the idea of “mental models”, our internal assumptions about how systems work. Before arriving in Madhya Pradesh, my suggestion was that major barriers to healthcare in rural India were likely to be knowledge gaps among patients or a lack of motivation among healthcare workers.

But three weeks of fieldwork in Chhindwara dismantled that idea. I met frontline health workers—ASHAs, ANMs, Anganwadi workers—who were diligent, invested, and often underpaid. I spoke to women who were well-informed about government health services but couldn’t access them because of real-life trade-offs: Who would cook if they left home for two weeks to admit their malnourished child to a Nutrition Rehabilitation Centre (NRC)? Who would take care of their other children? What if they had previously been treated disrespectfully at a health centre?

None of this was visible in my original mental model. But it was the reality on the ground. And that’s the first lesson I’ll carry with me: no model, however well-intentioned, survives first contact with the lived experience of others. We cannot build good policy without first undoing what we think we know.

Even within one district in one state, the diversity of challenges was striking. In some blocks, monsoon floods prevent patients from reaching higher-level facilities. In others cases, the problem is understaffed primary health centres or poorly maintained equipment. In still others, the barrier is trust, shaped by prior interactions or caste dynamics.

I remember one woman who mentioned feeling more comfortable seeking care because the nurse at her facility was from her own caste. It was a reminder that healthcare is not just technical: it is social, political, and deeply personal. A one-size-fits-all policy, even a well-meaning one, risks missing the mark entirely if it fails to account for these local realities.

One thing I appreciated about TAF’s approach is its commitment to data-led localisation: training and support vary across districts, tailored to the specific gaps identified in performance data. This is hard work, it’s slower, less scalable on paper, but it’s what makes the work effective. Good health policy doesn’t travel well unless it learns to speak the local language, literally and figuratively.

One of the most illuminating insights for me was seeing how healthcare isn’t a series of separate interventions but a network of touchpoints. A shortfall at one level (say, a PHC not equipped to handle basic deliveries) creates overload at another (tertiary hospitals), which then leads to burnout, worse care, and ultimately, diminished trust in the entire system. Over time, people internalise these failings and become less likely to seek care, even when they need it.

Trust, I came to realise, is not a soft outcome but a structural one. And it is built or eroded at every interaction: in how patients are spoken to, whether their concerns are heard, and whether they are treated with dignity. Respectful care is not a bonus, it’s a requirement for effective health systems. And yet, it’s the dimension most likely to go unmeasured.

TAF’s work, particularly its emphasis on mentoring, data use, and frontline capacity-building, tries to strengthen each node of the system so that the whole becomes more than the sum of its parts. Working on the experience of care, we were essentially trying to measure trust to make it visible, monitorable, and improvable.

The fieldwork we conducted in Chhindwara involved interviewing 20 mothers and caregivers, which served as a pilot for designing TAF’s future experience of care monitoring tool. The conversations revealed both successes and structural barriers: from poor provider behaviour to household-level responsibilities that prevent women from accessing services, especially when they require multi-day facility stays like those at NRCs.

We also spoke with caregivers who did make it to NRCs, often thanks to support from their partners or in-laws. These stories highlighted the role of unpaid care work, gender norms, and informal support systems in shaping healthcare uptake.

After returning to Delhi, I spent my final weeks analysing these interviews, identifying patterns in responses, and flagging limitations in the questionnaire we had tested. I compiled these insights, alongside a literature review of validated tools from India and globally, into a draft monitoring framework that TAF can take forward. I also led a session on how to conduct literature reviews for TAF’s Knowledge Management team, and presented my final learnings in an all-team sharing session, where colleagues from Chhindwara joined in virtually.

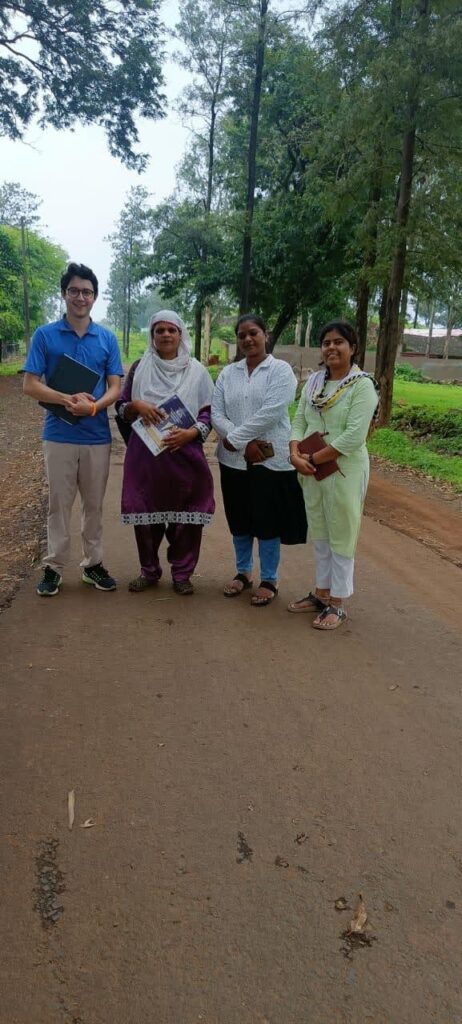

Of course, none of this work would’ve been possible without the support of the Chhindwara team. Over long car rides to field sites, they shared their favourite music, taught me phrases in Hindi, and helped me understand local cultural nuances that don’t show up in datasets. Their hospitality, from everyday guidance to a farewell cake and pizza party on my last day, made me feel like part of the team.

This internship was more than a project. It was a relationship with a place, with a people, and with the practice of public service.

I came to India with questions about scale, systems, and solutions. I leave with more nuanced ones: about whose voices we amplify, what trade-offs we ask people to make, and how we define what quality really means. I’m especially grateful to the women who shared their stories with us—openly, honestly, and with the hope that things could change.

For me, more than a blueprint, policy is a dialogue. To The Antara Foundation, and to everyone I met this summer: thank you for helping me see this more clearly.