A Community Health Centre (CHC) the third point of contact in the rural public health system

“The maternal mortality rate (MMR) of India is 167 per 100,000 live births and the infant mortality rate (IMR) is 34 per 1000 live births. These are important statistics and you must know them”, the professor instructed a class of about forty listless students aspiring to be public health professionals. I dutifully made a note of those numbers and kept memorising until they became embedded in my head. After all, these are important statistics a public health professional must know. But the thing with statistics is that they are just numbers. Although undoubtedly important numbers, they also make it easy to overlook that there are people- real people behind these numbers. In my opinion, these evolving statistics, while extremely instructive, fail to capture stories. Maybe that is why they are forgettable. I believe that it is always the stories one remembers, not the numbers.

Can you spot the Anganwadi centre?

It has been a month since I moved base to Jhalawar, a district nestled close to the Rajasthan-Madhya Pradesh border. Now that I look back, perhaps it was the pursuit of finding such stories that motivated me to do the Fellowship. And while certainly aplenty, I was simultaneously confronted by stories of despair and hope. India has managed to reduce its MMR from 254 to 167 over a period of seven years, which is no small feat. But the number is still way too high, and lot remains to be done. Simple, well-known public health interventions hold the promise to help reduce MMR in the country. For instance, basic interventions such as organising and maintaining hygienic conditions in the labour room and having skilled staff can significantly contribute to prevention of maternal deaths. Yet, some health facilities I visited were struggling to ensure even these basic requirements for various reasons ranging from shortage of staff to lack of leadership. These stories strengthened my belief that, in public health, the solutions are (almost) always low and not-so low hanging fruit.

An Anganwadi worker with the multiple registers needed for her work

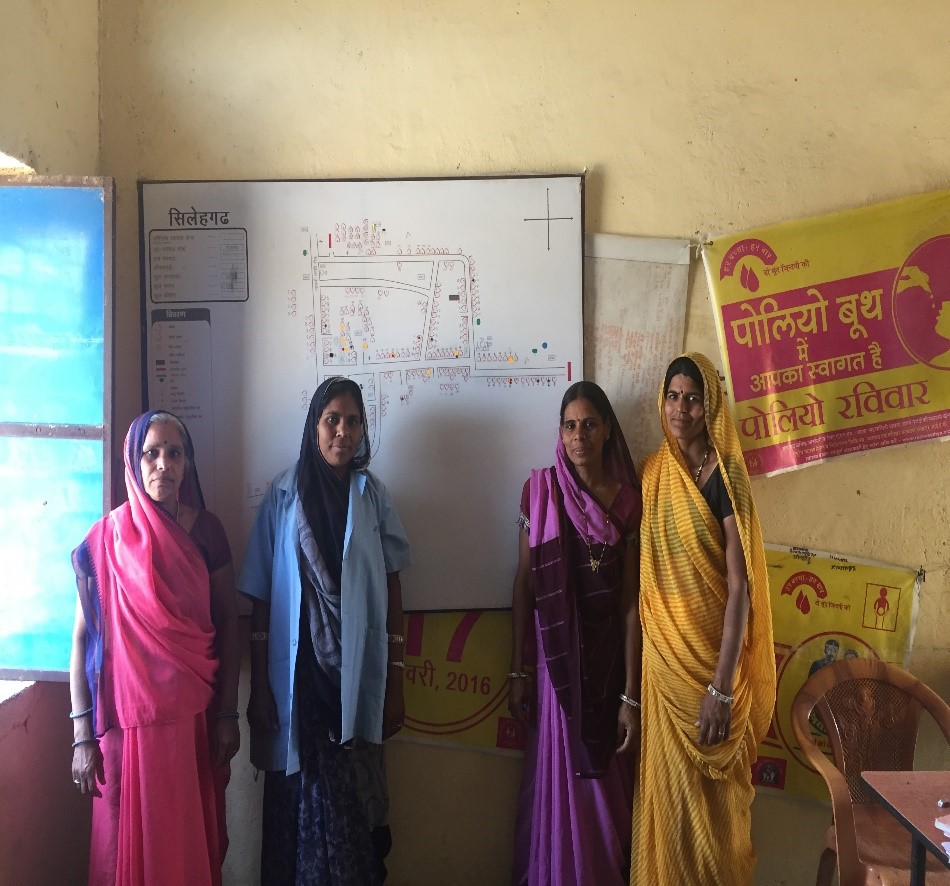

The reduction in MMR tells us about the reduction in maternal deaths but does not tell us the stories of those millions of health workers who made this possible. I witnessed the relentless efforts of health workers who often travelled long, arduous paths to ensure that no mother or child is deprived of the services they deserve. The stories of these health workers, who are women themselves, left an impression on me. These women, like millions of working women around the country, carried the responsibility of their households and the health of the areas they worked in. In all my visits so far, for reasons I am yet to understand, I saw no male health worker.

The cadre of front-line workers (FLWs) responsible for improving health in the country

Working on maternal and child health in rural Rajasthan allowed me to witness brazen inequities which sometimes angered, at other times sobered me. The impassive manner in which people spoke about sickness, death and associated tribulations particularly struck me. It seemed as if they had accepted these as inevitable; not because it did not affect them, but because they probably did not have the luxury to mourn for long. I witnessed first-hand why maternal and child health is unquestionably a gender issue and how caste and class profoundly influence maternal and child health outcomes.

Two Apasi children playing while those belonging to Dalit community look on

I was taught that availability, accessibility, and affordability is the mantra to alleviate public health problems, achieve universal health coverage, and improve people’s lives. My experiences, however, challenged several such dictums that I held. It made me question whether this will hold true if the health workers are not empathetic and the health system is oblivious to the needs of the people it serves. The past few weeks have enabled me to ponder about the scalability of public health interventions. I have been trying to understand how to ensure minimum quality when scaling up, contextualise interventions to suit local needs, and what makes for a successfully scaled intervention. In my opinion, the effectiveness of an intervention can be determined not by mere change in numbers, but when stories, inpidual and collective, change. And I hope that the next 11 months of my fellowship are filled with many such stories.

A child looks on from the Anganwadi centre during Village health and nutrition day (VHND)

Rithika Sangameshwaran was a fellow with the Antara Foundation

Disclaimer: The article has been written in personal capacity, and the views and opinions expressed are those of the author